Is There Finance After Sanctions?

It’s been 5 months since Russia invaded Ukraine, and most Russians are still reeling from the economic sanctions imposed on the nation. From the voluntary “operation suspension” by the likes of Visa and Mastercard to the removal of several Russian banks from the SWIFT network, private and public institutions alike have swiftly acted to punish the nation’s government for its actions, as well as the rest of the Russian populace. This article will explore how both the average consumer and the financial market have adapted to these changes.

Foreword

It is extremely important for me to stress that this article isn’t political. There is a plethora of people infinitely more qualified than me to dissect the political nature of the Ukraine-Russia regional conflict. However, having lived in Russia for most of my life, I believe that I am in the unique position to pull back the “Financial Iron Curtain”, to bring back firsthand accounts about how the average (non-oligarch) Russian is living with these sanctions.

I also must warn potential readers that most of this article is unsourced. I am the primary source for a lot of this information, simply because this situation is so niche. While I tried my best to make sure all the information is accurate and up-to-date, in the post-sanction financial world, so many of these things change so quickly that a lot of information might be out of date within a matter of months, weeks, or even days. Take what I say with a grain of salt.

The Financial Iron Curtain

When Visa and Mastercard announced that they were pulling out of Russia, the entire country was taken by surprise. In a world where borders matter less and less, especially in the realm of finance, most people relied on Russian banks’ generous “no foreign transaction fee” policy to conduct business abroad. However, immediately after the sanctions were enacted, Russians living abroad and foreigners living in the country were suddenly cut off from the easiest way to access their funds.

At the same time, a vast number of companies pulled out of the country (over 1000 according to Yale), severely crippling the average Russian’s quality of life. While I’m sure most people can live without Spotify or YouTube Premium, there is no denying the impact of payments for more essential services being unable to go through. If you were renting a server from AWS or Google Cloud, sitting the SAT or IELTS, buying airplane tickets or booking hotels, ordering spare parts for your car from Europe, or doing anything remotely related to cross-border commerce and travel, you now had to scramble to find a way to pay for services rendered without having them inexplicably taken away.

There is, however, a large problem: the average Russian citizen does not have a bank account abroad. According to Russia’s Federal Tax Service, only 700 thousand citizens have bank accounts abroad. To put this number into further perspective, only 543 thousand Russians have at least a second citizenship, according to Russia's Ministry on Internal Affairs. Even if we assume that 2/3 of people with said luxuries don’t report them to the government, that’s still a measly 1.45% of the country with foreign bank accounts. It is impossible to accurately count these numbers, but even with the most generous assumptions, just shy of 99% percent of the country is currently behind the financial iron curtain, unable to make payments abroad.

Card Tourism

Now that we know the scale of the problem, it’s not surprising that “card tourism” is becoming more and more popular in Russia. Russia is part of the CIS, an EU-like trading and economic bloc consisting of most post-Soviet states. Many CIS member nations have visa-free agreements with Russia, allowing Russian citizens to stay for 90 days without filing for a visa. Because of this, and the fact that only Russia and Belarus have been affected by the latest round of sanctions, a new sanction-evading loophole has appeared: a Russian citizen can travel to a CIS member state for a week and open a bank account there, at a bank not sanctioned by the West. This is called "card tourism".

Many CIS banks are taking advantage of the situation by imposing high account maintenance fees and charging large sums of money for express debit card issuance. One such bank is UniCredit Bank in Armenia. According to a relative who has travelled to Armenia to open an account there in March, here’s how the fees for nonresidents stack up:

“50k dram [~123 USD] yearly maintenance, 125k dram [~306 USD] for express card issuance (they issued a card within half a day). If you can wait 5 days, they issue the card for free.”

All in all, the average person would have to pay about 1000 USD, including flights, hotels, and all other associated fees and taxes. To illustrate why this is unfeasible for most people, we can look to the US. The average US resident is better off than the average Russian resident in almost every way: life expectancy, GDP per capita, etc. Despite all this, 56% of Americans cannot afford to cover a surprise $1000 expense, according to Bankrate. If the average American can't afford to engage in card tourism, how is the average Russian expected to do the same?

The answer is simple. They aren't.

SWIFT Shenanigans

Opening a bank account abroad, however, is just the first half of the problem. In order to use a foreign account, there needs to be a way to it to be funded. Russia has its own P2P fast payments system - SBP - but that system works only in rubles and doesn't work outside of the country. Russian wire transfers don't work outside of the country, either. That leaves three ways to transfer money out of the country:

- Withdrawing rubles, exchanging them for an arbitrary currency (in the case of Armenia, Armenian drams) and depositing them abroad in person. This is obviously impractical to do, even for the possible largest amounts.

- Using certain banks' internal money exchange systems or external networks like Unistream and KoronaPay (popular Western networks like MoneyGram, Western Union and the like have all pulled out of the country). In this case, you will lose money thrice:

- Exchanging RUB to an arbitrary currency using a poor exchange rate.

- Commissions to the bank/payment network for using their services.

- Exchanging the arbitrary currency back to USD at an even poorer exchange rate.

- Using a network specifically designed to alleviate this pain: SWIFT.

However, out of Russia's top 10 consumer-oriented banks, only 3 haven't been disconnected from the SWIFT network: Gazprombank, Raiffeisen, and Rosbank. Russia's most popular bank according to banki.ru, Sberbank, was one of the first to be sanctioned, which means that a very sizable portion of Russians cannot even begin to transfer money out of the country.

Assuming they find a bank enough with a low enough commission rates, using a resource like санкциям.net, there is still the problem that Western banks are scrutinizing every Russian transfer. Take for example Gazprombank. According to data crowdsourcing website ohmyswift.ru, most recent transfers have either refunded or didn't arrive at the recipient's account yet. There is also a note at the top of the page:

"24.07.2022 There is unofficial information about problems with [Gazprombank's] dollar correspondent bank since July 20. Transfers could take longer than a month."

Correspondent banks are intermediaries in the SWIFT system. Rather than having payment agreements with every single bank everywhere around the world, most banks use a correspondent bank that has agreements with both the sender and recipient bank when sending an international wire transfer. This keeps costs reasonably down for everyone in the ecosystem.

However, this means that your money could pass through two or more intermediary banks that can halt or refund your transfer as they please. It doesn't matter if you're transferring money to Asia or Africa, if a single European or American correspondent bank handles money originating from Russia, they will ask for additional documentation, or have the option to refund your transfer outright.

This is an issue because regular account holders have no relationship with correspondent banks, since they work on a B2B level directly with regular banks. This means that while they are incentivized to make sure the payment goes through via their commission, they have no legal obligation to make it go though, and can decline or delay your payment as they see fit.

Looking back at OhMySwift, we can see that transfers take 1-22 days to complete, with most recent ones being refunded or "hanging" (still being processed). This unreliability plagues all new SWIFT transactions out of Russia. Because of the way the network works, there is no way to ask your bank to avoid Western correspondent banks, meaning that every outgoing Russian international wire from now on is essentially a leap of faith.

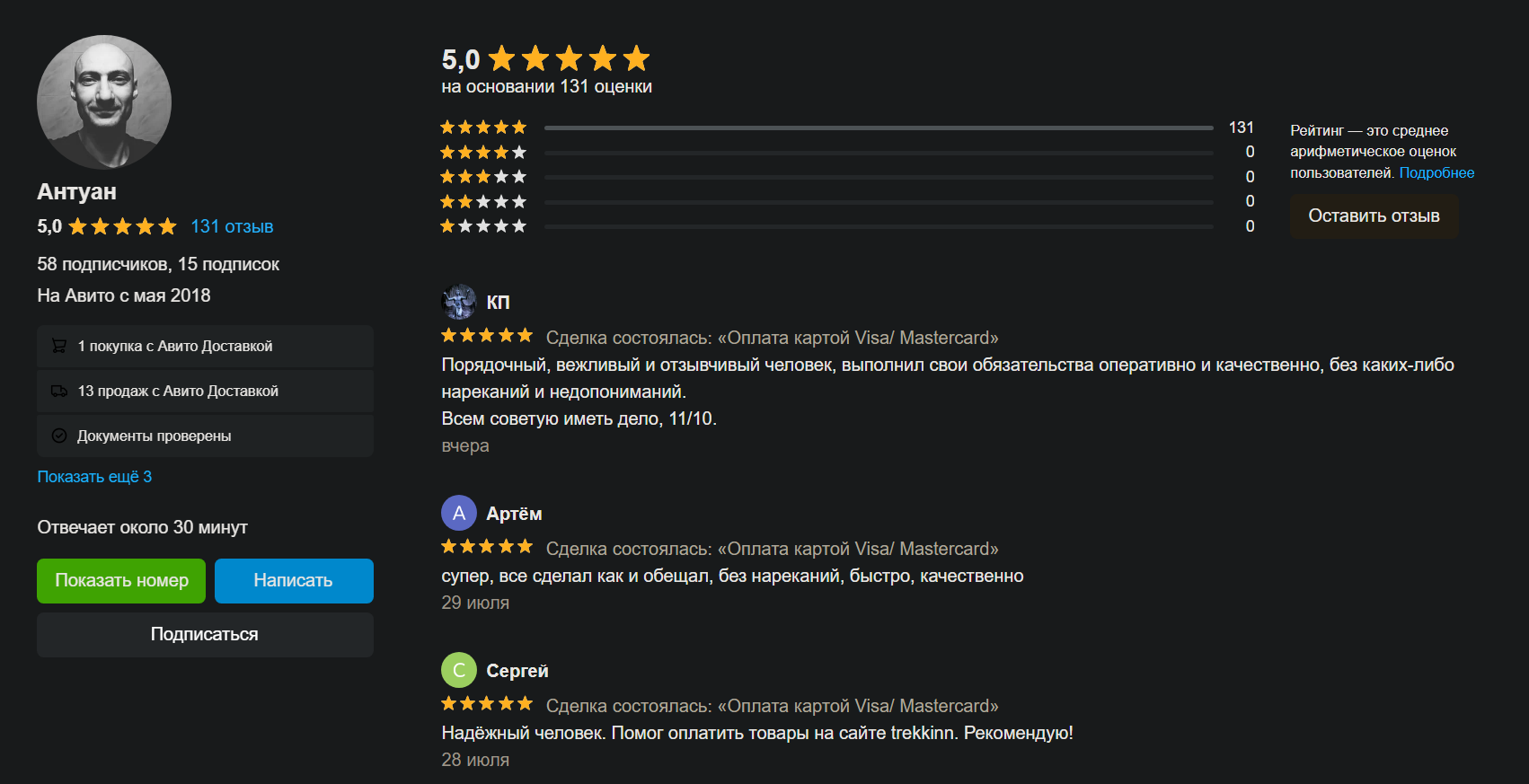

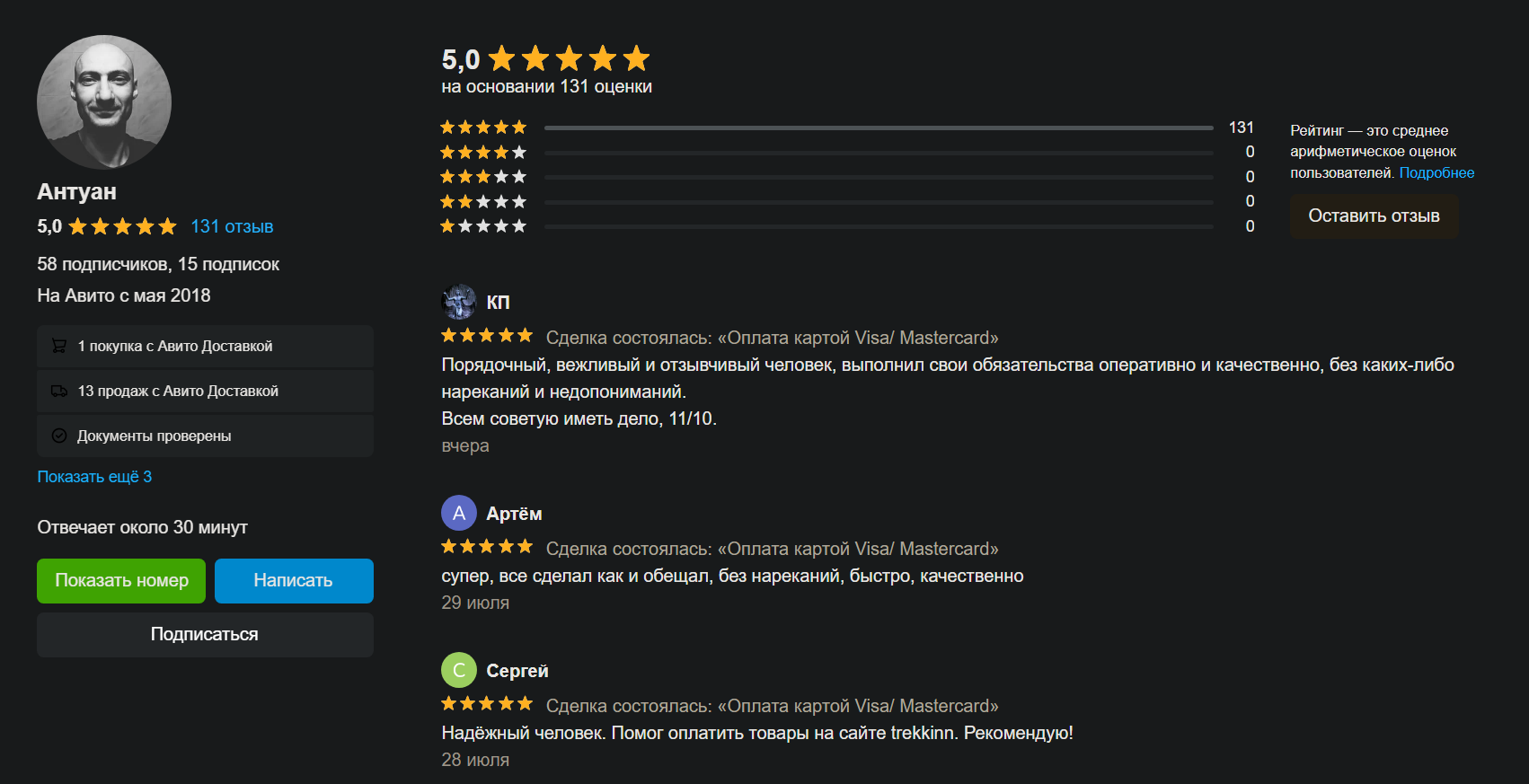

Vaguely Extortion

Just like in the banking world, tough times have created a ripe environment for intermediaries to take advantage of the situation. One such example can be found on Avito: Russia's answer to eBay and Craigslist. Freelancers and average people alike have found a home on the website, where you can do anything from sell a couch to offer your professional services. Recently, however, sellers with foreign bank accounts have realized their unique position and have begun offering their services on the website.

Here's how a typical "helping pay with a card abroad" (a popular search term for this type of activity of Avito) transaction goes through:

- The client finds a seller using Avito's search and contacts them with the price of the item or the subscription they want.

- The seller gets back to the client with the price in rubles, usually with some sort of markup for their services.

- The client pays upfront and then receives either the item they pay for or a refund if the transaction is unsuccessful.

Because the exchange rate from rubles to whatever foreign currency is public knowledge, sellers cannot make money like most banks do via quoting an inflated exchange rate. Instead, they use whichever bank's exchange rate is the highest at the time of the transaction to convert from an arbitrary foreign currency to rubles, and then add on their commission at the end.

Typically, market forces would work to lower these commission rates, and, in the banking world, this is typically the case. Most Russian banks use the mid-market exchange rate for foreign transactions, and usually waive foreign transaction fees on debit/credit cards entirely. However, because the vacuum left by Visa and Mastercard's exit from the market is so extreme, sellers can get away with 10-25% commission rates and high (500-1000 RUB or 8-16 USD) transaction minimums.

Avito also has a rating system that clients can use to leave feedback, but systems like this can easily be abused. It is not impossible for a scammer to create a new profile, buy a bunch of fake 5-star reviews, and then scam a big fish that comes along. Most sellers require payment upfront to execute the transaction (this is a common Russian business practice, since, according to proverb, "Nothing strengthens faith in a person like advance payment"), and a financially unsavvy buyer could easily fall for a scam of this sort.

There is also the matter that this financial activity is strictly in the legal grey zone. Since sellers are regular individuals paid in rubles via P2P payment systems in Russia and execute their transactions using their own personal cards tied to foreign bank accounts, there is no practical way for sellers to execute KYC checks on their customers. There is also no practical way for tax agencies on either side of the financial iron curtain to tax these transactions, since they are cross-border, cross-jurisdiction, and are often not executed via traditional means.

Since the SWIFT network is extremely unreliable when it comes to moving money out of the country, most sellers use cryptocurrency instead of wire transfers. This makes it even harder for tax agencies to track, especially if sellers use P2P exchanges. While the break-even margin for cryptocurrency transfers is anywhere from 0.5-7% depending on the time of day and volatility of the markets (speaking from personal experience), crypto payments move incredibly fast, taking anywhere from 10 minutes to one hour to move money out of Russia and into the West. This allows sellers to have empty bank accounts at both the start and end of the business day, lowering the effective risk of bank account closures.

Because so much of the seller's business is dependent on moving money out of the country cheaply and quickly, these individuals operate at a speed and scale unheard of in the financial world. They utilize every mean at their disposal to cut costs; means that are inaccessible to businesses too reliant on reporting every transaction for taxation and regulatory purposes. Private companies simply cannot fill this gap because the regulatory risk is too high (banks will not want to work with a business whose main goal is to tip-toe the line around international sanctions, and the workflow required to keep these transactions legal would stifle any attempt to get into the market).

This means that the core of this business is made up of a few dozen individuals willing to take the risk for making these types of transactions, attracted only by profit and not by the willingness to help their fellow citizens. Their actions could vaguely be classified as extortion - since, for most people, there is simply no other alternative.

Dollar Drain?

Despite the crazy lengths people are willing to go in order to pay for things abroad, there is also the problem of moving money out of the country. While individuals can use cryptocurrency to move money around, most people aren't proficient enough with these means, and prefer to use the traditional tools at their disposal.

In order to avoid immediate inflation and a deficit of foreign currency in the nation, the Central Bank of Russia barred nonresidents and companies from "unfriendly nations" from transferring money out of the country, with foreign banks scrambling to rehire staff after they realized Russia would not let them pull out so easily, according to Reuters. Regular people could only transfer $5000 a month abroad at the start of the way, but this limit was later raised to $150 000, and now $1 million, according to Russian news agency Vedomosti.

While the Central Bank says that this limit has been raised due to "a stable position on the internal foreign currency market", it's unclear whether this is actually the case, or if the bank is trying to diminish an already significant dollar drain with a sheer show of confidence.

Despite the Central Bank's measures to inspire confidence, there is now essentially a grey market for foreign hard currency in Moscow. Only people who have had foreign currency accounts since the 8th of March can withdraw hard cash from bank offices, according to Russian news agency RBK, with banks disabling ATM withdrawals. At that time, most big banks didn't have any foreign currency left in their ATM machines. Because of this, while the official exchange rate is set pretty low, most people cannot buy currency and withdraw it at that low rate from a bank, forcing them to buy currency at a markup from a third party.

We can also speculate why SWIFT transfers from Russia take so long. It might not entirely be the fault of Western partners, but also of Russian banks trying to avoid total devaluation of their foreign currency reserves. Several anecdotal cases have been reported of Russian banks claiming to have sent funds, but neither the correspondent or recipient bank having ever received them.

All this uncertainty around traditional banking has pushed people to explore cryptocurrency and alternative networks. It is unclear whether banks are lying in order to save their assets or at the behest of the Central Bank or, indeed, if they are even lying at all. One thing is for certain - very shady things are happening with foreign currency in Russia.

Conclusion

We will never know if Visa and Mastercard's decision to pull out of Russia was self-imposed, fearing violating AML/sanctions policies, or, perhaps, forced by the US government. At the end of the day, there is something to be said about how two US-based companies control the vast majority of the world's consumer transactions.

While allowing two players to consolidate the card payment industry has allowed for financial globalization at an unprecedented scale, we magically seemed to forget the main pitfall of such centralization: we do not control our own money.

Your bank can close your account, your credit card issuer can pull out of the country, your government can become sanctioned... Your hard-earned currency can become a virtual paperweight with the click of a button and the issuance of a single press release.

This is the reality on the ground in Russia. The average citizen has no recourse and no way out. Shady intermediaries with the means to skirt sanctions will offer their services at a markup regardless of the legality. Some people got around the restrictions, others are still stuck without a working card.

I personally wouldn't inflict a punishment like this upon my worst enemy.